We cannot doubt that self-interest is the mainspring of human nature. It must be clearly understood that this word is used here to designate a universal, incontestable fact, resulting from the nature of man, and not an adverse judgment, as would be the word selfishness. The moral sciences would be impossible if we perverted at the outset the terms that the subject demands.

Human effort does not always and inevitably intervene between sensation and satisfaction. Sometimes satisfaction is obtained by itself. More often effort is exerted on material objects, through the agency of forcesthat Nature has without cost placed at man's disposal.

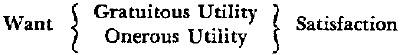

If we give the name of utility to everything that effects the satisfaction of wants, then there are two kinds of utility. One kind is given us by Providence without cost to ourselves; the other kind insists, so to speak, on being purchased through effort.

Thus, the complete cycle embraces, or can embrace, these four ideas:

Man is endowed with a faculty for improvement. He compares, he looks ahead, he learns, he profits by experience. If want is a pain, and effort too entails pains, there is no reason for him not to seek to reduce the pains of the effort if he can do so without impairing the satisfaction that is its goal. This is what he accomplishes when he succeeds in replacing onerous utility by gratuitous utility, which is the constant object of his search.

Man is endowed with a faculty for improvement. He compares, he looks ahead, he learns, he profits by experience. If want is a pain, and effort too entails pains, there is no reason for him not to seek to reduce the pains of the effort if he can do so without impairing the satisfaction that is its goal. This is what he accomplishes when he succeeds in replacing onerous utility by gratuitous utility, which is the constant object of his search.Our self-interest is such that we constantly seek to increase the sum of our satisfactions in relation to our efforts; and our intelligence is such—in the cases where our attempt is successful—that we reach our goal through increasing the amount of gratuitous utility in relation to onerous utility.

Every time progress of this type is achieved, a part of our efforts is freed to be placed on the available list, so to speak; and we have the option either of enjoying more rest or of working for the satisfaction of new desires if these are keen enough to stir us to action.

Such is the source of all progress in the economic order. It is also, as we easily comprehend, the source of all miscalculations, for progress and miscalculation both have their roots in that marvelous and special gift that God has bestowed upon man: free will.

We are endowed with the faculty of comparing, of judging, of choosing, and of acting accordingly. This implies that we can arrive at a good or a bad judgment, make a good or a bad choice—a fact that it is never idle to remind men of when we speak to them of liberty.

We are not, to be sure, mistaken about our own sensations, and we discern with an infallible instinct whether they are painful or pleasurable. But how many different forms our errors of judgment can take! We can mistake the cause and pursue eagerly, as something sure to give us pleasure, what can give us only pain; or we can fail to see the relation of cause and effect and be unaware that an immediate pleasure will be followed ultimately by greater pain; or again, we can be mistaken as to the relative importance of our wants and our desires.

We can give a wrong direction to our efforts not only through ignorance, but also through the perversity of our will. “Man,” said de Bonald,∗ is an intellect served by bodily organs.” Indeed! Do we have nothing else? Do we not have passions?

When we speak, then, of harmony, we do not mean that the natural arrangement of the social world is such that error and vice have been excluded. To advance such a thesis in the face of the facts would be carrying the love of system to the point of madness. For this harmony to be without any discordant note, man would have to be without free will, or else infallible. We say only this: Man's principal social tendencies are harmonious in that, as every error leads to disillusionment and every vice to punishment, the discords tend constantly to disappear.

A first and vague notion of the nature of property can be deduced from these premises. Since it is the individual who experiences the sensation, the desire, the want; since it is the individual who exerts the effort; the satisfactions also must have their end in him, for otherwise the effort would be meaningless.

The same holds true of inheritance. No theory, no flights of oratory can succeed in keeping fathers from loving their children. The people who delight in setting up imaginary societies may consider this regrettable, but it is a fact. A father will expend as much effort, perhaps more, for his children's satisfactions as for his own. If, then, a new law contrary to Nature should forbid the bequest of private property, it would not only in itself do violence to the rights of private property, but it would also prevent the creation of new private property by paralyzing a full half of human effort.

Self-interest, private property, inheritance—we shall have occasion to come back to these topics. Let us first, however, try to establish the limits of the science with which we are concerned.

I am not one of those who believe that a science has inherently its own natural and immutable boundaries. In the realm of ideas, as in the realm of material objects, everything is linked together, everything is connected; all truths merge into one another, and every science, to be complete, must embrace all others. It has been well said that for an infinite intelligence there would be only one single truth. It is only our human frailty, therefore, that reduces us to study a certain order of phenomena as though isolated, and the resulting classifications cannot avoid a certain arbitrariness.

The true merit consists in the exact exposition of the facts, their causes and their effects. There is also merit, but a purely minor and relative one, in determining, not rigorously, which is impossible, but rationally, the type of facts to be considered.

I say this so that it may not be supposed that I wish to criticize my predecessors if I happen to give to political economy somewhat different limits from those that they have assigned to it.

In recent years economists have frequently been reproached for too great a preoccupation with the question ofwealth. It has been felt that they should have included as part of political economy everything that contributes, directly or indirectly, to human happiness or suffering; and it has even been alleged that they denied the existence of everything that they did not discuss, for example, the manifestations of altruism, as natural to the heart of man as self-interest. This is like accusing the mineralogist of denying the existence of the animal kingdom. Is not wealth—i.e., the laws of its production, distribution, and consumption—sufficiently vast and important a subject to constitute a special field of science? If the conclusions of the economist were in contradiction to those in the fields of government or ethics, I could understand the accusation. We could say to him, “By limiting yourself, you have lost your way, for it is not possible for two truths to be in conflict.” Perhaps one result of the work that I am submitting to the public may be that the science of wealth will be seen to be in perfect harmony with all the other sciences.

Of the three terms that encompass the human condition—sensation, effort, satisfaction—the first and the last are always, and inevitably, merged in the same individual. It is impossible to think of them as separated. We can conceive of a sensation that is not satisfied, a want that is not fulfilled, but never can we conceive of a want felt by one man and its satisfaction experienced by another.

If the same held true of the middle term, effort, man would be a completely solitary creature. The economic phenomenon would occur in its entirety within an isolated individual. There could be a juxtaposition of persons; there could not be a society. There could be a personal economy; there could not be a political economy.

But such is not the case. It is quite possible, and indeed it frequently happens, that one person's want owes itssatisfaction to another person's effort. The fact is that if we think of all the satisfactions that come to us, we shall all recognize that we derive most of them from efforts we have not made; and likewise, that the labor that we perform, each in our own calling, almost always goes to satisfy desires that are not ours.

Thus, we realize that it is not in wants or in satisfactions, which are essentially personal and intransmissible phenomena, but in the nature of the middle term, human effort, that we must seek the social principle, the origin of political economy. It is, in fact, precisely this faculty of working for one another, which is given to mankind and only to mankind, this transfer of efforts, this exchange of services, with all the infinitely complicated combinations of which it is susceptible in time and space, that constitutes the science of economics, demonstrates its origins, and determines its limits.

I therefore say: Political economy has as its special field all those efforts of men that are capable of satisfying, subject to services in return, the wants of persons other than the one making the effort, and, consequently, those wants and satisfactions that are related to efforts of this kind.

Thus, to cite an example, the act of breathing, although containing the three elements that make up the economic phenomenon, does not belong to the science of economics, and the reason is apparent: we are concerned here with a set of facts in which not only the two extremes—want and satisfaction—are nontransferable (as they always are), but the middle element, effort, as well. We ask no one's help in order to breathe; no giving or receiving is involved. By its very nature it is an individual act and a nonsocial one, which cannot be included in a science that, as its very name implies, deals entirely with interrelations.

But let special circumstances arise that require men to help one another to breathe, as when a workman goes down in a diving bell, or a doctor operates a pulmotor, or the police take steps to purify the air; then we have a want satisfied by a person other than the one experiencing it, we have a service rendered, and breathing itself, at least on the score of assistance and remuneration, comes within the scope of political economy.

It is not necessary that the transaction be actually completed. Provided only a transaction is possible, the laborinvolved becomes economic in character. The farmer who raises wheat for his own use performs an economic act in that the wheat is exchangeable.

To make an effort in order to satisfy another person's want is to perform a service for him. If a service is stipulated in return, there is an exchange of services; and, since this is the most common situation, political economy may be defined as the theory of exchange.

However keen may be the want of one of the contracting parties, however great the effort of the other, if the exchange is freely made, the two services are of equal value. Value, then, consists in the comparative estimation of reciprocal services, and political economy may also be defined as the theory of value.

I have just defined political economy and marked out the area it covers, without mentioning one essential element: gratuitous utility, or utility without effort.

All authors have commented on the fact that we derive countless satisfactions from this source. They have termed these utilities, such as air, water, sunlight, etc., natural wealth, in contrast to social wealth, and then dismissed them; and, in fact, since they lead to no effort, no exchange, no service, and, being without value, figure in no inventory, it would seem that they should not be included within the scope of political economy.

This exclusion would be logical if gratuitous utility were a fixed, invariable quantity always distinct from onerousutility, that is, utility created by effort; but the two are constantly intermingled and in inverse ratio. Man strives ceaselessly to substitute the one for the other, that is, to obtain, with the help of natural and gratuitous utilities, the same results with less effort. He makes wind, gravity, heat, gas do for him what originally he accomplished only by the strength of his own muscles.

Now, what happens? Although the result is the same, the effort is less. Less effort implies less service, and less service implies less value. All progress, therefore, destroys some degree of value, but how? Not at all by impairing the usefulness of the result, but by substituting gratuitous utility for onerous utility, natural wealth for social wealth. From one point of view, the part of value thus destroyed no longer belongs in the field of political economy, since it does not figure in our inventories; for it can no longer be exchanged, i.e., bought or sold, and humanity enjoys it without effort, almost without being aware of it. It can no longer be counted as relative wealth; it takes its place among the blessings of God. But, on the other hand, political economy would certainly be in error in not taking account of it. To fail to do so would be to lose sight of the essential, the main consideration of all: the final outcome, the useful result; it would be to misunderstand the strongest forces working for sharing in common and equality; it would be to see everything in the social order except the existing harmony. If this book is destined to advance political economy a single step, it will be through keeping constantly before the reader's eyes that part of value which is successively destroyed and then reclaimed in the form of gratuitous utility for all humanity.

I shall here make an observation that will prove how much the various sciences overlap and how close they are to merging into one.

I have just defined service. It is effort on the part of one man, whereas the want and the satisfaction are another's. Sometimes the service is rendered gratis, without payment, without any service exacted in return. It springs from altruism rather than from self-interest. It constitutes a gift and not an exchange. Consequently, it seems to belong, not to political economy (which is the theory of exchange), but to moral philosophy. In fact, acts of this nature are, because of their motivation, moral rather than economic phenomena. Nevertheless, we shall see that, by reason of their results, they pertain to the science with which we are here concerned. On the other hand, services rendered in return for effort, requiring payment, and, for this reason, essentially economic, do not on that account remain, in their results, outside the realm of ethics.

Accordingly, these two fields of knowledge have countless points in common; and, since two truths cannot be contradictory, when the economist views with alarm a phenomenon that the moralist hails as beneficial, we can be sure that one or the other is wrong. Thus do the various sciences hold one another to the path of truth.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Your Comments