What should be the size of the state?

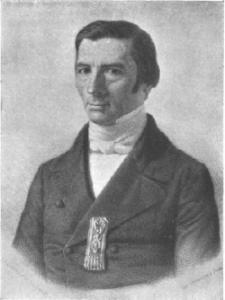

Frédéric Bastiat

Bastiat asks the fundamental question of political economy: what should be the size of the state? (1850) |

In his incomplete magnum opus Economic Harmonies (1850) Frédéric Bastiat asks the fundamental question of political economy: what should be the proper size of the state? His answer is that it should limit its functions to a very “small circle” of activity which would include only defence and policing:

The first question to be asked, then, as we begin the study of political science is this: What are the services that should remain in the realm of private activity? What are those that should fall within the domain of public or collective activity? That question amounts to this: Within the great circle that we call “society,” what should be the circumference of the smaller circle we call “government”?

The full passage from which this quotation was taken can be be viewed below (front page quote in bold):

But what we actually observe is that public services or government action increases or decreases according to time, place, or circumstances, from the communism of Sparta or the Paraguay missions to the individualism of the United States, with French centralization as a midpoint along the way.[More works by Frédéric Bastiat (1801 – 1850) and on 19th Century French Liberalism]

The first question to be asked, then, as we begin the study of political science is this:

What are the services that should remain in the realm of private activity? What are those that should fall within the domain of public or collective activity?

That question amounts to this:

Within the great circle that we call “society,” what should be the circumference of the smaller circle we call “government”?

It is evident that this question is connected with political economy, since it requires the comparative study of two very different forms of exchange.

Once this problem is solved, there still remains another: How can public services best be organized? We shall not consider this question, since it falls entirely within the field of government.

Let us examine the essential differences between private services and public services, since this is a necessary preliminary to determining what should be the logical line of demarcation between them.

This entire book up to the present chapter has been devoted to showing the evolution of private services. We have seen that it is, implicitly or explicitly, based on this formula: You do this for me, and I will do that for you; which implies a double and mutual consent regarding what is given and what is received. The notions of barter, exchange, appraisal, value, cannot, therefore, be conceived of without freedom, nor freedom without responsibility. Each party to an exchange consults, at his own risk and peril, his wants, his needs, his tastes, his desires, his means, his attitudes, his convenience—all the elements of his situation; and nowhere have we denied that in the exercise of free will there is the possibility of error, the possibility of an unreasonable or a foolish choice. The fault is imputable, not to the principle of exchange, but to the imperfection of human nature; and the remedy is to be found only in responsibility itself (that is, in freedom), since it is the source of all experience. To introduce coercion into exchange, to destroy free will on the pretext that men may make mistakes, would not improve things, unless it can be proved that the agent empowered to apply the coercion is exempt from the imperfection of our nature, is not subject to passion or error, does not belong to humanity. Is it not evident, on the contrary, that this would be tantamount not only to putting responsibility in the wrong place, but, even worse, to destroying it, at least in so far as its most precious attribute is concerned, that is, as a rewarding, retributive, experimental, corrective, and, consequently, progressive force? We have also seen that free exchange, or services voluntarily received and voluntarily rendered, constantly increases, thanks to the effect of competition, the relative proportion of gratuitous utility to onerous utility, the domain of common wealth in relation to the domain of private property; and we have thus come to recognize in freedom the power that in every way promotes equality, or social harmony.

http://oll.libertyfund.org/?option=com_staticxt&staticfile=full_quote.php%3Fquote=295&Itemid=275

No comments:

Post a Comment

Your Comments